by Kalpana Mohan (India Currents, February 2011,www.indiacurrents.com)

Indian Americans will routinely discuss their political leanings, trade notes on wily ways to gyp the taxman, tell one another about the cheapest grocery store for buying almonds, and argue about the best cruise deal for Alaska. However, if there’s one topic they’re not exactly dying to debate—it is death.

The first wave of Indian immigrants that arrived here from India in the 60s and 70s is fast ageing. Death has begun to knock on their doors at least as often as taxes. As Zoe Alameda, a funeral director at the Alameda Family Funeral and Cremation in Saratoga, CA, points out helpfully, most people have no idea if what they have left is five minutes or 55 years. Her one word of advice is: PLAN. Alameda says that planning ahead for the inevitable can ease the pain and confusion for your loved ones and spare them the emotional turmoil of second-guessing what you would have wanted.

Cultural inhibitions make planning for one’s passing largely taboo in the Indian American community, but shouldn’t we devote as much time to this subject as we do to the other areas of our lives? Here is a primer to help begin the conversation.

Planning for Your Passing

1. Make a Will or Trust:

A Living Will lets you outline important healthcare decisions in advance, such as whether or not to remain on artificial life support. A Living Will includes a complimentary Health Care Power of Attorney that allows you to appoint someone you trust to make critical health care decisions for you.

A Last Will, an important part of an estate plan, is used to distribute property to beneficiaries, specify last wishes, and name guardians for minor children. It is an important part of any estate plan. Without one, the courts will make these critical decisions for you.

A Living Trust is used to transfer property to beneficiaries. But unlike a last will, a living trust is not usually subject to probate court, which can take years and cost thousands in court fees. A Living Trust includes a free Last Will and Testament to name guardians for minor children and specify last wishes.

2. Complete an AHCD and POLST Form:

Completing an Advance Health Care Directive (AHCD) is important for all individuals over 18 years of age if ever they are in a position where they cannot speak for themselves, such as an accident or severe illness. An AHCD allows individuals to appoint an agent who has the power of attorney to make care and treatment decisions on their behalf, and give instructions about their health care wishes. Alameda points us to the Terri Schiavo case where a legal battle between the wishes of her husband and her parents involved numerous legal appeals which could been avoided with an AHCD.

The Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) program is designed to improve the quality of care people receive at the end of life. It is a communication of patient wishes to a doctor and a promise by healthcare professionals to honor those wishes. A POLST is not the same document as an AHCD; POLST is a new form introduced in 2009 that may only be completed by a doctor. An AHCD is a form you complete yourself. Your doctor can tell you if your medical condition warrants a POLST.

3. Create an “In Case of My Death” Folder:

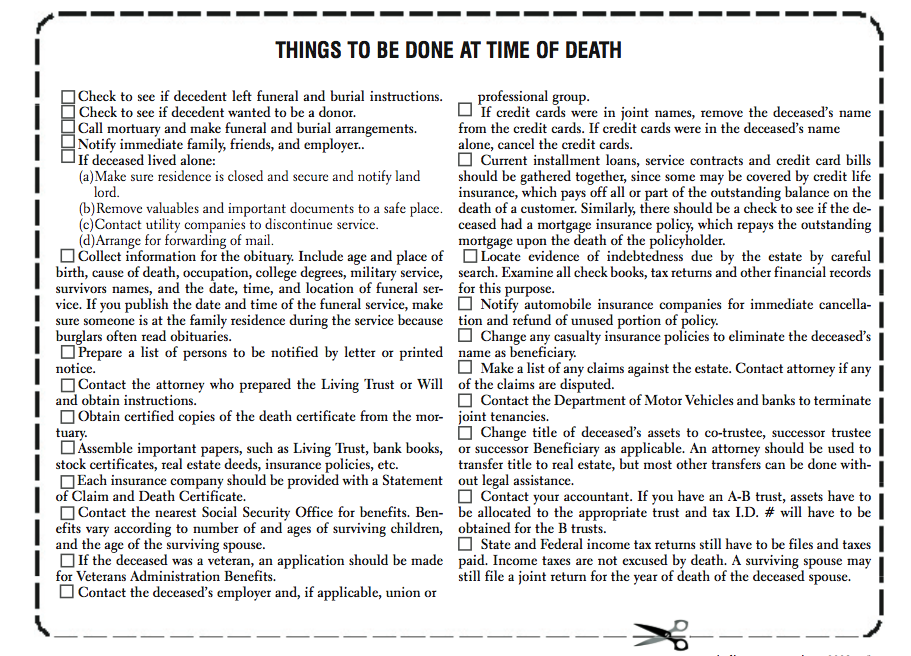

The folder should contain financial details, life insurance, bank accounts, investments, social security number and military records. Alameda says parents should tell their grown children where the physical folders are kept along with the location of any virtual files on a computer.

Vandana Kumar of San Jose, who lost her husband, Rajiv, 10 years ago to lung cancer (it was eight months from diagnosis to death) is grateful to her husband for his meticulous bookkeeping both during their life together and after his diagnosis. “In addition to explaining the details to me before he went into surgery, he made sure that my brother-in-law knew all the details of the financial folder as well,” Kumar says.

4. Plan Your Funeral or Cremation Ahead:

Planning ahead offers peace of mind for you and your family. What most people don’t realize is that dying is at least as expensive as taking a vacation. Today, the most basic funeral service will run a family about $7,000 (10 times the cost of a service in 1960) and if you want to go in pomp and style, it makes sense to make your wishes known well ahead by planning the details with a mortuary.

Selecting a casket (a requirement even for a cremation) can be mortifying because of the variety. Some people would kill to lie in a $13,000 solid dark mahogany exterior with a pearl velvet handcrafted interior, but others may go online to Walmart to order the cheapest one. “People from your community typically go for the most basic,”says Ronald Davey, a director at Alameda Family Funeral. It turns out that in death as in life, Indian Americans are downright practical.

When Death Strikes

Families that know a death is imminent must arrange for a preliminary meeting with the funeral director of a chosen mortuary. The funeral director will sit down with the family to discuss everything that needs to be done when the event finally occurs.

In case the death is unexpected, a dispatcher at a mortuary transfers the body from the home to the mortuary upon request; following the transfer, a meeting is scheduled during business hours. In an unexpected death, if the deceased did not belong to a hospice or was not under a doctor’s care for a medical condition, a coroner is also called in by a doctor, a nurse, or a police officer to confirm the cause of death. Alameda says she cannot stress enough the importance of having elderly family members visiting from other countries bring with them their medical history from their attending doctor back home.

A QUICK SUMMARY OF DIFFERENT SCENARIOS

Death in a Hospital, Nursing Home or Other Institution:

The nursing or medical Staff should take care of all necessary medical and legal steps. Notify the medical facility of the name of the funeral home handling the arrangements so they can be called when it’s time to transfer the decedent into their care.

Anticipated Death at Home:

Someone who has a terminal illness may want to remain at home and will elect to have hospice care. Let hospice know the name of the funeral home handling the arrangements so they can be notified of the death. The family may want to make prearrangements with the funeral home before the death so that they are not overwhelmed with the many important decisions at the time of death.

Unanticipated Death at Home or Elsewhere:

Immediately call 911. The police and emergency medical personnel will determine the necessary procedures. Often the police can then release the decedent directly to a funeral home. In certain circumstances, the body may need to be sent to the Medical Examiner/Coroner’s office to determine the exact cause of death.

The Evolution of Funeral Services in the United States

As the country’s demographics shift, funeral and cremation services have evolved along with them. According to the National Funeral Directors Association, cremation is on the rise in the United States, thanks to the changing preferences of immigrant communities and mainstream Americans as well–from 25 percent in 1999 to 35 percent in 2007.

Funeral directors are now also sensitive to the traditions of immigrant Indians, many of whom are Hindu. Alameda, who visited India last year to watch Hindu rituals, says funeral directors are well aware of the urgency of the disposition of the dead body in Hindu custom. But, she warns, in the United States the paper chase between the funeral home, the doctor or hospital, and the Department of Health requires time. “Families need to know that because of the protocol with the death certificate and the permit from the health department, the paper work takes a minimum of one business day,” she says.

In America, the final disposition (cremation or burial, as the case may be), cannot begin unless a death certificate and a disposition permit have been issued. While death rites are often performed at the home of the deceased in India, here in the United States the funeral home (mortuary) is where all the rites take place, with the exception of disposition. In rare cases, some funeral homes offer disposition services on site.

When a death happens, the body is transferred to the funeral home. The next of kin arranges with the funeral home to plan funeral or cremation services. The funeral home then prepares and files the certificate of death with the Department of Vital Records making the death “legal.” The funeral home also obtains a disposition permit for the body and then the final disposition (cremation or burial, as the case may be) takes place.

As a goodwill gesture to the communities they serve and as a practical business move, mortuaries in many parts of the country are revamping their offerings to suit the needs of their customers. The Fremont Memorial Chapel in Fremont, California, which has served the Indian-American population for over fifteen years has set aside a special room for Hindu and Muslim families to wash dead bodies. “We have a dedicated prep room just in case families want to bathe their loved one with special unguents,” says Jeff Orozco, funeral director and embalmer at Fremont Memorial Chapel.

Another resource is the Final Journey seminar organized by financial advisor Sandeep Varma and Hindu priest Dharmasetu Das (http://finaljourneyseminars.com). The idea came from San Diego resident Ravi Sahay when a heart attack in 2005 issued a wake-up call for his own mortality. The free seminar is now available at various locations in California.

Prepping For the Final Journey

When a death has occurred at home and the family wants to hold on to the body of its loved one in their home for visitors to pay their last respects, Alameda suggests placing it in a well-ventilated location to stave off decomposition. Since the decay begins right after death, Alameda advises transferring the body to a mortuary at the earliest.

A state law mandates that funeral homes refrigerate or embalm a body within 24 hours of its receipt. Embalming is not required by law. Yet there are reasons why some Indian American families choose to do the embalming. “If they are waiting for relatives to arrive from out of the country and it’s going to be four or five days, embalming offers a much better presentation of their loved ones,” says Davey of Alameda Family Funeral. If a body is not embalmed, the mortuary refrigerates it until the morning of the funeral rites.

A funeral home facilitates the services for the family of the deceased and bends to their needs. “I can’t tell you how many Easter weekends I have worked for Hindu families because they don’t celebrate Easter but that day was convenient for them for the service,”Alameda says. In such a job, the staff often begins to identify with the grieving families. “I get really connected with the families especially when I’m helping them dress their loved one and they begin to tell stories of the person,” says Jessica Burroughs, embalmer at Alameda Family Funeral. “We’re not here just facilitating, we are becoming a small part of these families for a little bit.”

Burroughs is well versed in dressing up people from any part of the world and keeps up with changing custom and tradition by attending conferences at the National Funeral Directors Association. “I always ask people how the sari is draped in the region of India that they’re from,” she says.

Seema Ramanathan of Fremont recalls giving her father’s traditional mundu and kurta to the staff at Fremont Chapel of Roses just before his last rites ceremony. “We couldn’t believe how well they dressed up my dad,” she says.

Most funeral homes work with several Hindu priests in the area and recommend them if the family has not arranged one on its own. In the case of a Hindu family, they will charge a standard funeral service fee along with a casket and cremation fee.

When the death certificate is issued, the mortuary schedules the funeral service and disposition. Caskets are required even for cremation; after the funeral service, the hearse is taken in a procession to the crematory led by mortuary staff where the family member is given an opportunity to press the button of the cremation chamber. When they press the button, the door opens out, and they witness the casket going into the retort (chamber). “Sometimes families will stay and see the whole process and they’ll want to watch the sweepout too,” says Davey, referring to the remains of bones and ashes in the chamber. Often the families are taking the remains back to India by flight. Note that there are several stringent requirements from the Government of India for repatriation of human remains.

WHAT THE INDIAN CONSULATE REQUIRES

For transportation of human remains (body of the deceased), the following are required:

(1) the passport of the deceased;

(2) a certified copy of the death certificate (by registrar of birth & death, or vital statistics); embalmer’s certificate (funeral home certificate stating that the body has been embalmed in accordance with the international shipping and that the body has been placed in a hermetically sealed container with zinc liner and wooden outer container) duly notarized;

(3) a no communicable disease certificate from the Department of Health stating that the deceased did not have any communicable diseases/contagious diseases;

(4) a burial/transit permit; and

(5) a fee of $60 for U.S. nationals; $1 for Indian nationals. For transportation of human remains (ashes), the following are required:

(1) the passport of the deceased;

(2) a certified copy of the death certificate (by registrar of birth & death, or vital statistics);

(3) the cremation certificate; and

(4) a fee of $40 for US nationals; $1 for Indian nationals. As a goodwill gesture to the communities they serve and as a practical

Dignity in Death

For Hindus living in India, funeral rituals stretch over an elaborate 12-day process of mourning, during which immediate and extended family members gather to send their loved one into the next world with devotional songs, prayers and poor feeding. Indian Americans might wonder how their family will, one day, face their last journey in the United States in an alien ethos and a work-dominated culture that lacks the support systems we grew up with in India. Which immigrant Indian has not wondered if he or she really should die on American soil, many thousand miles away from the land that nurtured him or her at birth?

Seema Ramanathan’s experiences offer perspective on the matter. She compares the handling of her mother’s death from esophageal cancer in Mumbai with the supervision of father’s unexpected death from a stroke in Northern California. Whether it was the management of terminal care for her mother, or the treatment of her mother’s body upon death, or the bureaucracy of getting the death certificate, the family had to endure an inordinate amount of frustration at the time of bereavement.

In contrast, when her father died here in the SF Bay Area, the mortuary handled just about everything from the time of receipt of the body: overseeing all the paper work, guiding the family through the logistics and the grief and arranging for Hindu rites and cremation services. To Ramanathan, the process was smooth and reassuring at every point. “There was so much more dignity with my dad’s death and service. The process here was so much easier. I feel I’m at peace,” she says.